DISCLAIMER: Nothing on this website is legal advice for you. If you have legal questions, contact a lawyer.

Contents

BACKGROUND

If you haven’t already, watch our TEDx Talk. It makes the FAQs below easier to understand and follow.

What’s your project?

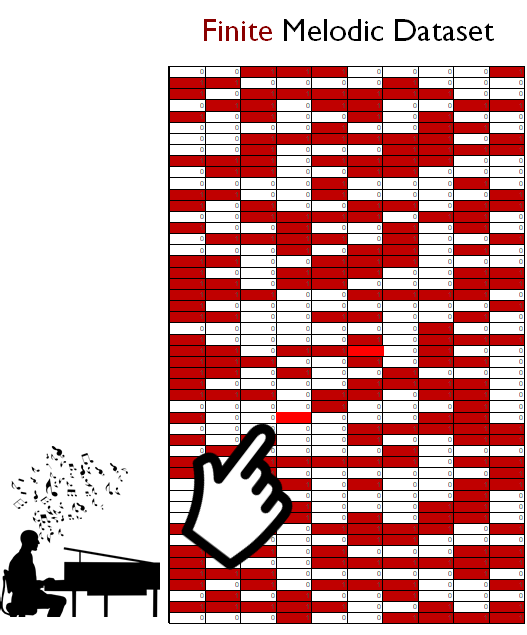

We’ve created an application to generate by brute force all mathematically possible melodies and write them to MIDI files. The application accepts various parameters (e.g., pitch, rhythm, length) to mathematically exhaust all melodies that have ever been — and are mathematically possible.

When our MIDI files were written to disk, they were copyrighted automatically. We then dedicated all newly created files (to which we have legal rights) to the Creative Commons Zero (CC0).

As such, this project may leave many (or perhaps all) melodies open for other songwriters to use without fear of being sued.

A diatonic scale has only seven pitches, and every melody ever created must work within that seven-note constraint. So the universe of possible melodies forms a grid. That grid is mathematical. It has existed since the beginning of time. And each time a songwriter writes a melody, that songwriter is merely plucking that already-existing melody from the already-existing melodic grid.

Over time, overlap is inevitable. When a songwriter (Adam) plucks a melody (Melody X), and then another songwriter (Beth) accidentally plucks the same melody, that results in lawsuits — even if Beth has never heard Adam’s Melody X.

Copyright law does permit “independent creation” (e.g., Adam and Beth each own independent copyright in their respective, identical Melody X). That’s in theory.

But in practice, Adam can claim that Beth “subconsciously infringed” Adam. And with internet distribution (e.g., YouTube, Spotify) nearly everyone has access to nearly every song.

So Beth is left in a near-impossible situation: proving a negative (“I’ve never heard Adam’s song”). How can Beth prove that she never heard Adam’s song playing over a supermarket loudspeaker?

For Beth to prove her independent creation, she must go to trial and spend legal fees up to millions of dollars. And even then, juries and judges might not believe her. They might find that Beth just “subconsciously infringed.” Unsurprisingly, Beth almost always loses.

We’d like to help fix that. Through our project, we want to help songwriters create more music.

Why are you doing this?

We’ve seen a flaw in the current copyright laws, described above, and we’d like that flaw to be remedied — to help songwriters. And since the current copyright laws result in uncertainty, we’d like our work to help increase certainty, allowing songwriters to make more music (with less fear of frivolous lawsuits).

Are you making money?

No. We’re trying to help songwriters and have not made any revenue or profit. We’re doing this for the love of music and justice. We want all songwriters to be able to make more music.

What have you created so far?

Thus far, we have created (and are in the process of generating) the following:

- Major octave — length 12

- Minor octave — length 12

- Chromatic octave — length 10

- Major/Minor 13 pitches — length 10

What are your goals?

The All the Music Project has several goals: some mathematical, some philosophical, and mostly legal. We discuss them below. Our primary overarching goal: help songwriters make more music.

How do you hope to help songwriters?

An innocent songwriter (e.g,. Beth) should be able to reference — and use — the open spaces we’ve established as a sort of “public commons.” This will be particularly helpful when an earlier songwriter (e.g., Adam) sues the innocent songwriter (e.g., Beth) over the earlier songwriter’s similar song (e.g., Adam’s Song 1) — particularly when Beth has never heard Adam’s Song 1.

Or perhaps Melody = Math = Fact = Uncopyrightable (or Thin Copyright). Maybe a melody is merely a number. And numbers are uncopyrightable. Then Adam and Beth can each independently create their works — as copyright law permits, at least in theory — without fear of “You stole my melody!” lawsuits.

What’s the primary legal question?

All the Music’s dataset includes billions of machine-created works. The entity All the Music LLC programmed the application and pressed “run.” The result is over 200 billion MIDI files. And we’re making more.

What is the status of those machine-generated works: copyrightable or uncopyrightable?

- IF copyrightable,

THEN All the Music has dedicated all works to which it has copyright into Creative Commons Zero (CC0). - IF uncopyrightable because Melodies = Math = Unoriginal/Facts = Uncopyrightable (Or Thin Copyright)

THEN all ATM melodies are uncopyrightable facts, available for others to use.

Under either scenario, we think that most (if not all) of the ATM dataset might be available for all songwriters to use.

That’s the heart of the legal issue. And we explore that question in more detail below.

How might this make a difference?

Here’s an example of a scenario that might play out:

- July 2019: Our All the Music project (ATM) has mathematically exhausted a large melodic dataset — which contains Melody X

- October 2020: Adam writes Song 1 — which contains Melody X

- November 2020: Beth writes Song 2 — which contains Melody X — but Beth has never heard Adam’s Song 1

- December 2020:

- Adam sues Beth over Song 2.

- Beth argues that because Song 1’s Melody X was in the public domain already — when ATM project generated it a year earlier, or as fact existing since the beginning of time — Adam cannot later copyright something (Melody X) that is either factual or has been in the public domain.

- This is similar to an argument where someone in 2020 might try (but would fail) to claim new copyright to:

- A prominent melody in Beethoven’s Fifth (which is in the public domain).

- Or a Gregorian chant

- Or a “new” sentence that happens to be identical to a sentence from Shakespeare.

- Claiming new copyright (a government-created monopoly) on a public-domain work alone (without more) is arguably impossible.

- So in the same way, Adam trying to claim copyright on Melody X is arguably impossible.

MELODY = MATH = FACTS = UNCOPYRIGHTABLE

Melodies are math: Finite combinations of notes/pitches

As noted above, the ATM Project’s dataset exhausts the mathematical possibility of various datasets. These include, amongst other datasets:

- Major octave — length 12

- Minor octave — length 12

- Chromatic octave — length 10

- Major/Minor 13 pitches — length 10

This covers nearly all popular melodies and the vast majority of chromatic melodies (including classical and jazz). The dataset is even more comprehensive if two or more of the ATM Project’s files are combined adjacently.

But even if our current dataset doesn’t cover a particular melody, our larger point is that melodies are merely math. Change the algorithm’s parameters (e.g., more pitches, longer melodies), and then that melody will be included. All melodic combinations are mere math.

What about rhythm?

Yes, rhythm usually makes a huge difference! Our most-recent dataset includes rhythm. Though under copyright law, rhythm doesn’t matter much.

Rhythm’s importance depends on context:

- For music theory/appreciation?

- For copyright lawsuits?

For music theory/appreciation: Absolutely! Rhythm is a strong contender (with pitch change) of “most important musical element.”

But in copyright infringement: Does rhythm really matter? To prove copying, copyright law doesn’t require the exact same rhythms; it merely requires “substantial similarity.” Songs with different rhythms can be “substantially similar.” And infringing.

In The Chiffons v. George Harrison, the songs had different rhythms:

But the court still held that Harrison infringed the Chiffons’ copyright — even though the rhythms were different. Under copyright law, they were “substantially similar.” Rhythm didn’t matter.

Consider this other scenario:

- Song A is an instrumental Jazz song (swing)

- Song B covers Song A, but as Pop (straight eighths)

- Song C covers Song A, but as Reggae (different syncopations)

- Song D covers Song A, but as Classical (lots of melismas and embellishments)

Same melody, but different rhythms.

Song A’s songwriter (Adam) sues the songwriter of Songs B, C, and D (David Defendant) for copyright infringement.

In those copyright lawsuits, can David (successfully) argue “Nope, different song and not infringement — we had completely different rhythms!”?

JUDGE: “Nice try, but all four songs are ‘substantially similar.’”

This is similar to Vanilla Ice’s argument — that his “Ice, Ice Baby” bass line had a pickup note, making it completely different than Queen’s “Under Pressure.” Nope: substantially similar.

If under copyright law, rhythmic variation can still be “substantially similar,” then to what extent does rhythm matter? Or is the primary element — for the purposes of copyright infringement — merely the change in pitch? To date, that’s what our All the Music project has cataloged.

And to the extent rhythm might matter (though it probably doesn’t), our newest dataset also includes rhythm.

Mashup: “Twinkle Baa ABCs”

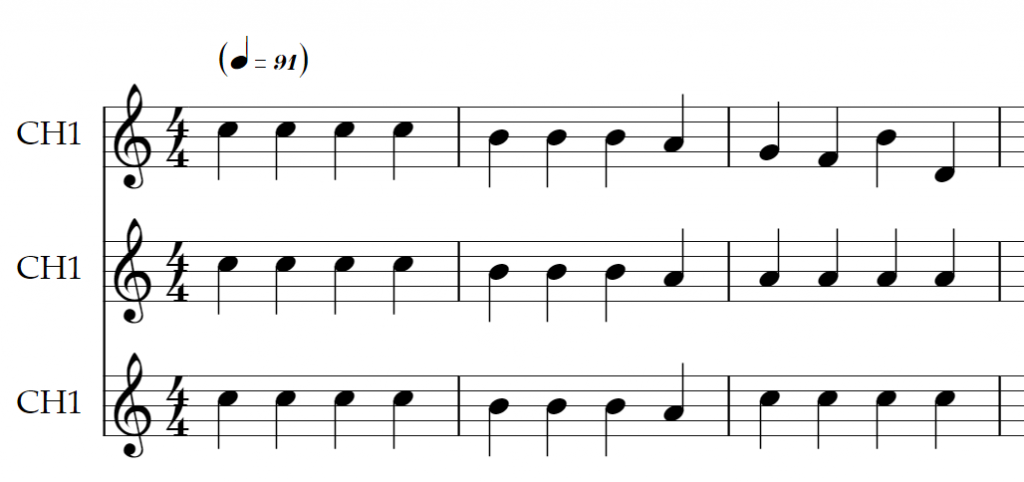

Consider this example: Many people have been surprised to realize that these three songs share the same melody.

- SONG 1. Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star

- SONG 2. Baa Baa, Black Sheep

- SONG 3. ABCs

Same melody, but different rhythms. See below:

The rhythmic difference stems from their different lyrics. Different words = different # of syllables = different rhythms. But the same melody.

If the “Twinkle” songwriter (Adam) sued the songwriter of “Baa” and “ABCs” (David), could David argue “Nope, see those different rhythms? No infringement!”

Copyright law doesn’t require that the songs/rhythms/pitches be “exactly the same” — the law only requires “substantial similarity.” Those three songs (Twinkle, Baa, ABCs) are all “substantially similar.”

Get out of infringement free: “I changed the rhythm!”

If changing rhythm were enough to avoid infringement, then David Defendant would merely need to:

- Change the words = syllable # = rhythms

- Change the pitch durations (rhythms)

- Take artistic liberties (e.g., jazz interpretation style, “leaning” on notes, expanding notes, contracting notes)

Done — no infringement! Except they would infringe. The melodies are still “substantially similar.”

ATM Project Melodies vs. Existing and Not-Yet-Existing Melodies

In the same way, compare:

- all melodies in the ATM Project’s datasets

- other popular melodies (existing now and not-yet-existing)

The melodies are all “substantially similar.” Like in Twinkle, Baa, and ABC: Rhythmic variation doesn’t matter.

Even so, our most-recent dataset includes rhythm.

Songs can be “unique” — even sharing the same melody

Importantly, the fact that “Twinkle,” “BAA,” and “ABCs” share the same melody blows people’s minds — discovering that, for decades, they hadn’t realized that the songs shared the same melody — demonstrates how these “stole my melody” lawsuits are absurd. Each song stands on its own. Few people realize they’re the same melody.

“Gotcha” melody similarity → lawsuits

Discovering these songs’ identical melody is essentially “gotcha!” (“Wow, I never realized that!”) Same with many of these “you stole my melody” lawsuits. Copyright law shouldn’t reward “gotcha.” And songwriters shouldn’t have to pay $500,000 to $1 million to defend against “gotcha.”

Merely using the same underlying pitches doesn’t make songs identical. They’re still different. And absent evidence of David consciously copying Adam, those songs should be non-infringing.

ATM Project’s “substantial similarity”

Our ATM Project melodies are “substantially similar” to every other melody. Especially since our dataset currently comprises and (and is the process of generating) these variations/combinations:

- Major octave: 8 pitches, length 12

- Minor octave: 8 pitches, length 12

- Chromatic octave 13 pitches, length 10

- Major/minor 1.6 octaves: 13 pitches, length 10

That’s today. Expanding is mere math. CPU + Time = More Melodies.

PROBABILITY: Why should the number of mathematical combinations matter?

Because the lower number of mathematical combinations, the more likely Beth is to accidentally also use the same Element X as Adam did. And for Beth to be sued unjustly.

If Element X has a 1/100 chance in showing up in a pop song, and if 1,000,000 songs are recorded annually (by both professionals and home-studio musicians on Soundcloud, Spotify, YouTube), then 10,000 songwriters are subject to a potential copyright-infringement suits annually.

So to the question “who cares about likelihood,” the answer might relate to:

- Number of mathematically possible combinations

- Likelihood of Beth accidentally overlapping Adam (stepping on a musical landmine)

How does probability relate to melodies/motifs?

A motif is a short melody. But the line between “melody” and “motif” is unquantifiable. Or at a minimum, we haven’t found quantification that has been blessed by a regulator or court.

Regardless of definition, the combinations of motifs/melodies are remarkably finite. Especially for shorter ones.

Three pitches in a 5-note sequence

= 3^5

= 243 possible combinations.

That’s remarkably few.

Reminder: Soundcloud currently has 200 million songs

What about harmony/chords?

A diatonic scale has only seven primary chords (discounting sevenths, suspensions, and other variations that are “substantially similar” enough that a defendant’s “I changed the V chord to V7” wouldn’t defeat copyright’s “substantial similarity” analysis).

In popular music, four chords are overwhelmingly common: I, IV, V, vi. So the odds of using those four are even higher.

See Hooktheory.com and its Popular Chord Progressions page.

Here’s the math:

[number of chords]^[number of chord changes]

So using My Sweet Lord as an example:

- Chorus has:

- 2 chords: A + Em

- 6 changes

- Verse has:

- 5 chords: A + D + Bm + F#dim + B7 + Em

- 9 changes

- So the combinatorial math plays out like this:

- IF song has 2-chord, 6-change chorus

THEN 2^6

= 64 chord combinations

- IF song has 5-chord, 9-change verse

THEN 5^9

= 1,953,125 chord combinations (less than 2 million)

- IF song has 2-chord, 6-change chorus

Reminder: Soundcloud currently has 200 million songs.

SONG FORM: What about song form or structure?

In isolation, how copyrightable is:

- VERSE + CHORUS + VERSE + CHORUS + BRIDGE + CHORUS x2

- Or an ABABAB structure?

- Or a 12-bar blues?

- Or call-and-response?

- Or any of the other popular song forms and structures?

What’s the probability of accidentally landing on one of the above?

Each seems pretty factual. Or akin to uncopyrightable scènes à faire.

What about other elements (e.g., lyrics, instrumentation, context, timbre)?”

Our project currently addresses only melodies. All musicians will probably agree that a song consists of far more than just the melody. Songs include melody + lyrics + harmony + instrumentation + context + timbre + other things I’m probably forgetting + magic. Of those, the only element that our project addresses is melody.

In isolation, how copyrightable is:

- A particular synth sound?

- A raspy voice?

- A slightly out-of-tune piano?

How copyrightable are those, even in combination with other factual elements (i.e., thin copyright)?

And if a song includes:

- Arguably factual Melody (e.g., descending scale)

- + Simple Quarter Notes

- + Synth sound

…does that combination constitute copyright infringement? Maybe, as Katy Perry found out.

If same descending scale would have been played on a piano, same result?

- Arguably factual Melody (e.g., descending scale)

- + Simple Quarter Notes

- + Piano, not Synth

Our All the Music project seeks to show — mathematically, and to non-musician judges/jurors — that a suit shouldn’t rest upon musical elements that everyone must use, as musical building blocks.

Because arguably Melody = Math = Fact = Uncopyrightable (or Thin Copyright). And perhaps musicians/songwriters should spend more of their time/efforts making more music, and less time suing.

UPDATE: On March 16, 2020, the court in the Katy Perry case reversed the jury verdict, as a matter of law, holding that the Plaintiff Flame’s ostinato melody was uncopyrightable. The court noted that “there is a narrow range of available creative choices,” infringement requires that the two works be “virtually identical.” Id. at 6. And “many if not most of the elements that appear in popular music are not individually protectable” — including elements that are “common or trite.” Id. at 9. “These building blocks belong in the public domain and cannot be exclusively appropriated by any particular author.” Id. at 10 (citing the Ninth Circuit’s Led Zeppelin case). Of Flame’s nine musical elements, the court held that “none of these individual elements are independently protectable.” Id. at 11. And “a pitch sequence, like a chord progression, is not entitled to copyright protection.” Id. at 13.

This decision — issued about a year after All the Music began its project, and about seven months after its TEDx Talk (which was widely covered in the press) — was the right one. Here’s hoping that more courts find similarly. And while we’re hoping: perhaps more of these cases can be dismissed early. After all, this finding is a “matter of law” — ripe for a an early-stage Motion to Dismiss.

What about “Thin Copyright”?

One might be tempted to create a variation on thin copyright for factual compilations:

IF combination of uncopyrightable facts is rare

THEN Author might get “Thin Copyright” over that compilation.

But how rare must that combination be? Because an innocent Beth might still use a common enough combination to accidentally step on a landmine.

Looking again at the George Harrison “My Sweet Lord” case:

- Melody: 3-note, 5-pitch sequence = 3^5 = 243 possible combinations

- Harmony: I + IV + V + I = 3^4 = 81 possible chord combinations

- Overall Song Form: Verse + Chorus (a gazillion songs since the early 20th century)

- Grace notes: Yes (like nearly every other popular song)

- Leitmotif: Yes, it has a hook.

- Structure: Yes, same as “song form”

So even under “thin copyright,” if Beth gets a non-musical judge/jury (likely), Beth is likely to lose. Over only 243 possible melody combinations. Or 81 possible chord combinations.

WHAT LAW APPLIES?

Today’s copyright law (not tomorrow’s)

The All the Music files exist today — in a fixed, tangible medium: MIDI files. So they are analyzed by copyright law that exists today.

TOMORROW. A forward-facing policy debate — like “motifs should be free to use as ‘elements’, but longer melodies should be protected” — might be a good policy argument. And those “what should happen” debates are interesting to discuss. For the future.

TODAY. But those forward-facing arguments don’t apply to the existing ATM Melodies — to which one must apply existing law. This isn’t hypothetical. The ATM Melodies exist today. Some have existed since mid-2019. And ATM keeps generating more.

Can we see me some example files?

Here are 8,192 MIDI files from the All the Music dataset.

- You can double-click them, and they’ll play on your computer — like an MP3

- You can also display them using software (e.g., a DAW) — like a PDF

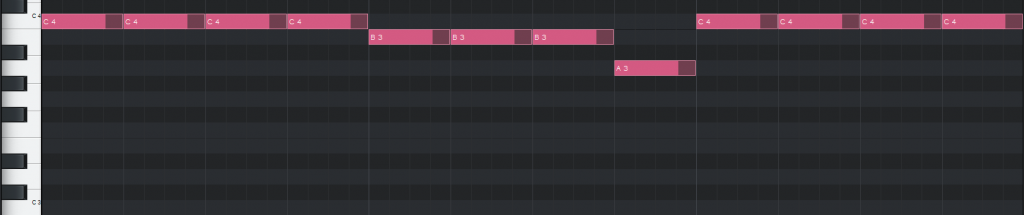

- Here’s an image of one of them in a DAW (Studio One, which is similar to Pro Tools).

And MIDI is also exportable to notation software (e.g., Finale, Notion). Below is an image of a few of the attached MIDI files, exported to Notion:

How are these MIDI files different than human-created MIDI files?

Functionally, they’re identical. The humans behind the All the Music Project created MIDI files. Other humans create other MIDI files.

- Compared with a human-created MIDI file, the All the Music MIDI files are functionally indistinguishable

- They all contain both:

- symbolic representations (like sheet music) and

- performance data (like sound recordings)

Because the All the Music Melodies and All the Music MIDI files exist today, the law must decide their legal status.Are those melodies/files:

- Copyrightable?

- Not copyrightable?

Since copyright is a legal concept, and since the files/melodies exist today, lawyers/judges/policymakers must look to the status of those files/melodies — not under future law/policy, but under current law.

COMPUTER-GENERATED COPYRIGHTABILITY

If created by a machine, is it copyrightable?

That’s a question that legal scholars have debated for decades. Here’s copyright Professor Samuelson’s seminal article from 1985. To date, U.S. lawmakers, policymakers, and courts haven’t yet provided a binding answer. Some non-binding guidance argues that machine-created works are not copyrightable: either as (1) unoriginal or (2) uncreative — where copyright law requires originality (and perhaps creativity). But some countries (e.g., the UK) appear to recognize copyright in machine-created works.

If ATM is copyrightable, then Creative Commons Zero (CC0). If ATM is not copyrightable, than anyone can use contents (as fact).

So we should look at the question as lawyers like professor Samuelson — and potentially a judge/jury — might:

- Are machine-created works (e.g., ATM Melodies as expressed in MIDI files) copyrightable?

- IF YES:

- THEN ATM Project’s machine-generated melodies are copyrightable

- And ATM Project has freed them for public use via Creative Commons (CC0)

- IF NO:

- BECAUSE Fact/Ideas, or…

- BECAUSE not Original/Creative…

- …THEN under either analysis (fact or unoriginal)

- The ATM project’s melodies would be uncopyrightable.

- Therefore, all songwriters can use those uncopyrightable ATM melodies freely (as one can use facts or any other uncopyrightable element freely)

- IF YES:

Under any legal analysis, the ATM melodies appear to be free for public use.

The above legal analysis, displayed as a flow chart, looks like this:

What other legal result might there be?

What about UK law?

This position is even stronger when considering other countries’ copyright laws. The United Kingdom appears to recognize copyright for:

The All the Music dataset is arguably both.

So there’s the logical possibility that:

- IF the UK recognizes All the Music’s dataset as copyrightable, either:

- as individual machine-created works

- OR as a database

- OR as both

- AND IF the Berne Convention requires signatory countries (e.g., US and UK) to recognize each other’s copyright,

- THEN must the US recognize the UK’s copyright recognition of the All the Music dataset’s individual melodies?

If these MIDI files are not copyrightable, as unoriginal/factual, then what does that mean for human songwriters?

Also consider the implications if All the Music’s machine-created melodies are NOT copyrightable — under the analysis above — as facts/ideas/unoriginal/uncreative:

IMPLICATION: Does that also mean that any other songwriter’s melody that is identical to an All the Music melody is also uncopyrightable as factual/unoriginal/uncreative?

- Are the same Melody X — in Flame’s “Joyful Noise” or Katy Perry’s “Dark Horse” and in the All the Music dataset — any different?

- Quarter notes

- Descending lines

- In fact, the All the Music dataset contains at least 8,192 MIDI files that contain a melody at issue in the Katy Perry “Dark Horse” case

- Those are the 8,192 files noted above — and provided here:

- See ZIP file containing those melodies

- See MIDI in DAW (below)

- See sheet music in Notion (below)

Do we — as a matter of public policy — want this result: Any other songwriter’s melody that’s the same an All the Music Melody is uncopyrightable, as factual/unoriginal?

- IF YES: Then we’ll have to consider those consequences

- IF NO: Then perhaps machine-created works (e.g., the ATM Melodies) are copyrightable (avoiding the “YES” result above). If so, then the ATM Melodies are now free under CC0.

Does the Feist Publications decision apply here?

The Feist case discusses the copyrightability (and non-copyrightability) of facts. Feist Publications, Inc v. Rural Telephone Service Co., Inc, 499 U.S. 340, 111 S.Ct. 1282, 113 L.Ed.2d 358 (1991).

Feist instructs that:

- “there can be no copyright in facts.” Id. at 340.

- “raw data are uncopyrightable facts” Id.

- “there is nothing remotely creative about arranging names alphabetically” Id. at 363.

Some might argue that, as applied to the ATM Project:

- The ATM Project’s dataset came from a simple algorithm

- Its output constitutes raw data

- There is “nothing remotely creative” about brute-forced numbers/melodies

If they’re right, then under Feist, the ATM dataset is mere facts. And if Feist renders the melodies factual, then that bolsters the ATM Project’s larger point:

- Melodies are mathematics (specifically: combinatorics),

- …which are facts,

- …which are not copyrightable (or have thin copyright)?

Under Feist, every songwriter/composer since the beginning of time has been arranging data — from the dataset of possible 8-tone or 12-tone combinations. Which are finite. And factual.

IF copyrightable, THEN original works = CC0. IF NOT copyrightable, THEN facts available for use.

Under either analysis, many (or all) of the ATM Project’s melodies are free for other songwriters to use:

- IF copyrightable,

THEN All the Music has dedicated all works to which it has copyright into Creative Commons Zero (CC0).

- IF uncopyrightable because Melodies = Math = Unoriginal/Facts = Uncopyrightable (Or Thin Copyright)

THEN all ATM melodies are uncopyrightable facts, available for others to use.

Is fact identification objective? Or subjective?

Some might still argue that copyright should only protect works that are human-generated.

Some songwriter tools will programmatically (through a computer) generate pleasing melodies — to help with writer’s block. Here’s an example.

As human-generated and machine-generated music becomes indistinguishable:

- How will that “humans only” rule be enforced?

- How will anyone know it’s machine-created?

Will “enforcement” mean (1) songwriter “human made” affidavits or (2) lawsuits?

- Between (1) human “Creative” melodies and (2) machine programmatic melodies — many are identical. And in the future, they’ll be increasingly indistinguishable.

- In the Katy Perry “Dark Horse” case, the disputed melody is simply quarter notes.

- The ATM Project’s dataset contains that identical quarter-note pattern (It’s a Melody X.)

- If the dataset’s Melody X is a fact (unable to be copyrighted), isn’t the Flame melody also an uncopyrightable fact?

- If it sounds/looks the same, is it the same? If an observer who — upon (1) hearing the melody and (2) seeing its sheet music — still cannot tell the difference between human-created and machine-created, are they really different?

- Origins types: So analyzing some categories of a melody’s origin — on order of melodic comprehensiveness:

Looking at each category:

- SOURCE 1: Human Creation.

- Under existing law, these melodies are probably copyrightable

- SOURCE 2: Writer’s Block Tools (e.g., Hookpad, Cthulhu)

- Example: Adam has writer’s block,

- So Adam uses a machine (e.g., Hookpad) to generate Melody X

- Adam then sings/records Melody X in Song 1

- Would Adam’s Melody X (contained in Song 1) lack copyrightability?

- How would anyone know?

- Example: Adam has writer’s block,

- SOURCE 3: ML Song Generators (e.g., AIVA).

- Example 1:

- A machine-learning neural network ingests public-domain works (e.g., Bach, Beethoven), and since it has learned that genre’s patterns, generates new orchestral pieces.

- Programmers create a generative adversarial network (GAN) to continuously create thousands or millions of melodies.

- Some of those melodies/harmonies/pieces are indistinguishable from human-created works.

- Example 2:

- Same as Source 2 example above — but rather than Hookpad, Adam instead uses AIVA.

- Example 1:

- SOURCE 4: ATM Project dataset

Example: Same as Source 2 and Source 3(2) examples above — but rather than using Hookpad or AIVA, Adam instead browses the ATM Project’s dataset.

Copyrightable or mere fact? Gotta sue — to find its origin!

As shown above, it is currently impossible to determine whether — even today — whether any melody is:

- Human created

- Machine created

So if under the “find its origin” theory, machine-generated works are uncopyrightable, how can we discover their machine-created origins?

- Beth to Lawyer: “Is Adam’s Song 1 copyrightable?”

- Lawyer: “It’s impossible to tell. He might have used a machine. To find out, we’d to have an expensive lawsuit, then in discovery, we’ll find out if he used a computer.”

So the “find its origin” theory continues the current scheme’s uncertainty:

- For litigants (and potential litigants), determining a melody’s copyrightability is impossible.

- Determining a “fact” is subjective (depends on origin). Not objective (see/hear the melody).

Like a quantum particle, does a melody’s copyrightability flip dynamically — upon the observer’s discovery of its origin?

If so, perhaps we can call this Schrödinger’s Melody X?

And if so, how does Beth know how Adam created Melody X?

- Litigation — with its expense and uncertainty? That leaves our uncertainty dilemma unresolved

- Songwriter Affidavits — collected by whom? Under what penalty?

Human incorporation/recording of machine-created works/elements

What if a human records some machine-created (1) Lyrics and (2) melodies — into a fully fleshed out song?

- How does the listener know that parts of the song have machine-created origins?

- At registration, how does the Copyright Office know?

These questions are embodied in this song:

Freight Train of Love (Ballad of These Lyrics Don’t Exist)

SOURCES AND CREDITS

- MELODIES:

- From the All the Music LLC Dataset (dedicated to Creative Commons CC0)

- HARMONIES:

- From the All the Music LLC Dataset (dedicated to Creative Commons CC0)

- LYRICS:

- Machine created from TheseLyricsDoNotExist.com — Lyric Production #351426

- See this text file, exported from the site

- ARRANGEMENT, ORCHESTRATION, LEAD VOCALS, BACKGROUND VOCALS, PIANO, GUITAR, AND ALL OTHER INSTRUMENTATION:

- Damien Riehl

- ENGINEERING, MIXING, MASTERING:

- Damien Riehl

- COVER ART:

- Damien Riehl

SELECTED LYRIC PARAMETERS

(from TheseLyricsDoNotExist.com)

- TOPIC: Love

- GENRE: Country

- MOOD: Happy

It’s a trite song, written and recorded in a few hours. But it contains at least a modicum of originality/creativity.

- Is the entire song copyrightable?

- If not the entire song, then

- What aspects are uncopyrightable?

- Why?

- If we hadn’t disclosed this song’s origins, would your answers to the above change?

- What if others songwriters don’t universally disclose computer-based songwriting tools?

- To the Copyright Office?

- To the copyright-infringement defendants (e.g., Beth)?

- Must Beth spend $100,000+ to find out?

- And then, Adam can simply say “Nope, never used any machine!”

- And how easily can Beth prove otherwise?

Today, songwriters are using machines to write songs. Tomorrow, that will increase. Those “hybrid” songs are indistinguishable from “pure human” songwriting.

So what can we do?

Ban Adam from using computer-based songwriting tools?

Good luck with that!

- If a tool (e.g., Hookpad, Cthulhu, AIVA, arpeggiators, Chord Track, All the Music) is available, then Adam (and songwriters like him) will almost certainly use it.

- The primary question: If we try to prevent using the tools, how can we ever ensure Adam’s compliance with “find its origin” enforcement?

Require Adam’s affidavit of non-machine creation?

One might suggest that the original songwriter (e.g., Adam) should be required to submit an affidavit certifying that Adam:

- Adam did NOT use a machine to create any part of Song 1

- Or that Adam:

- used a machine to create at least some parts of Song 1.

- and specify which particular parts

Some difficulties with that proposal:

- Who would collect it?

- Under the Berne Convention, copyright is automatic— as soon as the work is in a fixed, tangible medium.

- No registration (or anything else) required.

- So would Adam stuff his affidavit in his personal files?

- Or how would the average Adam even know that he needs to file an affdavit?

- Front end: Registration?

- Should we make this checkbox a condition of copyright registration: “I did not use a machine to give me an idea for any melody.”

- But what if Adam did use a machine?

- How would anyone know?

- And what’s to keep everyone from fudging the truth — on what would certainly become known in the industry as “the stupid ‘machine-created’ checkbox”

- Back end: Litigation?

- Should we make it a condition of being a copyright-infringement plaintiff to declare: “I, Plaintiff, did not use a machine to give me an idea for any melody.”

- But again, what if Adam did use a machine?

- So when Adam sues Beth, she would need to prove that Adam used a machine

- …requiring Beth to have to go through expensive discovery ($100,000+) to either:

- …to only then find out that Adam’s Melody X came from a machine (and is factual)?

- …or (more likely): never find out that Adam lied.

- Is that efficient? Is that desirable?

- Under the Berne Convention, copyright is automatic— as soon as the work is in a fixed, tangible medium.

This problem exists today.

- Today, AIVA-created songs/compositions exist.

- Today, might there also be hundreds (or thousands) of copyrighted songs that are performed/sung by humans — based on machine-created melodies?

- If so, would those melodic copyrights be invalidated?

And how many Top 40 hits wouldn’t be able to honestly claim that no creative machine was used in their creation? (e.g., automated arpeggiators, Studio One’s Chord track).

Potential solutions (really only one good option)

So of the potential solutions, which is viable?

- OPTION 1. Songwriters hide their use of “inspirational” tools (e.g., Hookpad, Cthulhu, AIVA, arpeggiators, Chord Track, All the Music) — for fear of losing their melodic copyright?

- OPTION 2. Songwriters attest in an affidavit (upon registration or litigation) that Adam did not use machines during the songwriting process?

- People who use machines will likely lie (or face the prospect of forfeiting copyright)

- …and those lies would be nearly impossible to detect.

- OPTION 3. Melodies = Math = Unoriginal/Facts = Uncopyrightable

- Easy

- Clear

- Unambiguous

Really, there’s only one solution: Option 3. And Option 3 is the ATM Project’s primary goal.

COPYRIGHT LOGISTICS: Creative Commons, Copyright Office Registration

How does one dedicate melodies to CC0?

One can claim copyright on a work, then use the Creative Commons process CC0 to designate its free use:

https://creativecommons.org/choose/zero/

But don’t you need to register with the Copyright Office?

Registration is unnecessary. Under the Berne Convention, formal registration isn’t required — as soon as the work is fixed in a tangible form of expression, it’s copyrighted automatically.

- IF copyrightable, THEN CC0.

- IF Melodies = Math = Unoriginal/Facts = Uncopyrightable THEN public domain since the beginning of time.

Don’t you need registration to enforce your copyright?

We’re not currently seeking to enforce copyright against anyone. Does CC0 designation to the public (or public use or public domain) require enforcement? Beethoven’s public-domain status doesn’t require enforcement. It merely is.

In the same way, CC0 works don’t require enforcement. They merely are. Any CC0 works should be freely usable. By anyone.

And that’s particularly true if they’re used as a shield (by defendants), not a sword (by plaintiffs).

Registration is unnecessary. Plaintiff-side enforcement is unnecessary.

Aren’t all symbols factual (e.g., combinations of factual ASCII symbols/characters make copyrightable language)?

True. But a question: For each symbolic dataset (e.g., language, melodies, chords), how many mathematically possible permutations?

- ASCII letters = 26 Roman letters

- English language = 117,000 words

- Atonal/jazz/classical melodies = 12 pitches (or 13 pitches, including top tonic)

- Diatonic melodies = 7 pitches (or 8 pitches, including top tonic)

So take some simple examples of mathematical permutations of each:

- 3 ASCII letters

= 26^3

= 17,576 3-letter combinations - 3 English words

= 117,000^3

= 1,601,613,000,000,000 (1.6 quadrillion) 3-word English phrases- “syntactically comprehensible” phrases = smaller, but still massive!

- 3-note atonal/jazz melodies

= 12^3

= 1,728 melodies - 3-note diatonic melodies

= 8^3

= 512 melodies

Longer phrases (e.g., 4 notes, 8 notes, 12 notes), do increase the number. But it’s still finite. And relatively small. Here’s a famous example:

George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord” = 8 notes

- 8^8 pitches possible (diatonic) = 16,777,216 melodies

- 3^8 pitches actually used = only 6,561 melodies

The important question, for each category:

- How long until we run out:

- …of 1,601,613,000,000,000 3-word phrases? That’ll take a while.

- …of 16,777,216 8-note, diatonic melodies?

- …of 6,561 George Harrison style 3-pitch, 8-note melodies?

- …of 1,728 possible atonal/jazz 3-note melodies (since the beginning of time)?

- …of 512 possible diatonic 3-note melodies (since the beginning of time)?

- And before we run out, what are the chances of overlapping accidentally?

Currently existing songs? Soundcloud = ~200million, adding 50M per year

- Each song has several melodies:

- Verse + Prechorus + Chorus + Bridge + Solos

- 2-10 melodies per song?

- 2x200M = 400 million melodies

- 10x200M = 2 billion melodies

- So millions of melodies added every year

- And only so many notes.

Melodies = Math = Unoriginal/Fact = Uncopyrightable (or Thin Copyright)

Isn’t a copyright claim without registration like claiming ownership of land without a deed or plat?

No, real property and intellectual property are different. For example, Beth can’t own Adam’s land accidentally. But Beth and Adam can accidentally use the same Melody X.

If Melody X is any of these:

- is CC0

- is in the public domain

- is uncopyrightable

…then nobody needs to “claim ownership.” Because no one currently owns them. They just are.

If All The Music’s songs are mathematically public domain or Creative Commons CC0, don’t people still need to access them?

Probably not.

Normally, for copyright infringement to occur, a copyright defendant (Beth) must have “Access” to Adam’s Song 1. So the argument might be “Because Adam didn’t hear the ATM Project’s Melody X, he’s free to copyright (and sue over) a new version of Melody X.”

But for works in the public domain or donated to CC0, the proper analysis goes back to the point above:

If a work (e.g., Shakespeare, Beethoven, Melody X) is in the public domain, may a new copy of that work (e.g., Song 1) monopolize what has been made free?

May a new work (e.g., Song 1) — standing alone, without additional creative additions — take take a work (e.g., Melody X); out of the public domain?

Under the law, probably not:

- Even if a new author has never accessed/read that Shakespeare passage

- Even if Adam has never accessed/heard/seen Beethoven

- Even if Adam has never accessed/heard/seen the ATM Project’s Melody X

CONTINUING TO PROTECT SONGWRITERS / PRODUCERS / MUSICIANS

Okay, but what’s left to protect?

Songwriters/producers/musicians can continue to make money — and will continue to be able to assert exclusive copyrights. Any assertion of copyright over many other non-melodic elements are likely unaffected.

- You can still sue over copyrightable lyrics. It’s nearly impossible to “accidentally” write the same lyrical phrases. The math is [number of English words] ^ [lyrical word length]. So the math for brute-forcing a 16-word phrase is 171,000^16=5.34e+88 (approaching the number of atoms on earth).

- You can still sue over cover songs.

- You can still sue over unauthorized use of recordings.

- You can still sue over insufficient streaming/radio royalties.

- You can still sue over every other copyrightable, non-melodic element.

Really, the only way that songwriters are affected by the All the Music project is up side: a shield, not a sword. If Beth’s Song 2 accidentally uses the same melody as Adam’s Song 1 — that Beth never heard — especially if her Song 2 contains different lyrics, harmonies, etc. Beth should be protected from accidentally stepping on a melodic landmine. Beth can point to All the Music’s work: Melody = Math = Fact = Uncopyrightable (or Thin Copyright).

How does your project affect someone unlawfully copying musical recordings?

It probably doesn’t. Those lawsuits will move forward, likely unaffected by us.

What about mechanical/performance royalties?

Under an ATM “music is math” world, song creators would likely continue to get mechanical/performance royalties (as they do now). Song 1 remains copyrightable and protectable. So if Song 1 is later:

- played on the radio

- streamed on the internet

- used in a commercial

- used in a film

…then the songwriter would continue to reap mechanical or performance royalties. Song 1 remains copyrighted (as it is today).

The only change might be that Melody X alone (one of the “sticks” in copyright’s “bundle of sticks”) isn’t copyrightable independently. The other “copyright sticks” remain intact. And songwriters retain the songs’ copyright.

How does your project affect lawsuits over non-melodic elements like “feel” or “groove”?

Those lawsuits are a travesty. And our currently created dataset might not impact them — since a jury’s apparent consideration of “groove” and mere “background chatter” don’t even allege melodic similarity. Our project currently addresses melodies. I’m not sure how we can fix those “groove” cases — beyond giving judges/jurors a better music education.

Perhaps if our proposition gains traction:

Melody = Math = Fact = Uncopyrightable (or Thin Copyright)

…then judges/jurors/regulators will extend that “only so many notes” idea to other “musical building blocks” like feel/groove.

SONGWRITER FAIRNESS

“But this just feels wrong — like it hurts songwriters.”

Whom does musical copyright protect? A primary beneficiary is songwriters. But music-copyright-infringement lawsuits are usually “Songwriter vs. Songwriter.”

- Today: Adam songwriter sues

- Tomorrow: Adam songwriter gets sued.

It’s a circular firing squad.

(Credit Howard Knopf for turning that phrase.)

Copyright should balance balance the rights of both songwriters:

- Protecting songwriters (e.g., Adam) from people stealing their songs (e.g., unlawful copying, unlawful distribution).

- Protecting innocent songwriters (e.g., Beth) from stepping on melodic landmines. (And from spending up to $2 million in legal fees.)

The current system punishes both Adam and Beth: Copyright law currently creates (1) uncertainty and (2) a “litigation tax.”

- Adam to Lawyer A: “Can I sue Beth?”

- Beth to Lawyer B: “Is Adam’s Song 1 copyrightable?”

- Both Lawyer A and Lawyer B: “Maybe. Depends on whether the judge or jury finds ‘substantial similarity.’ That’s usually a fact question. And the only way to determine fact questions: expensive discovery and/or trial.”

That’s our current uncertainty. That uncertainty helps litigators (lawsuits!), but it hurts all songwriters/labels/publishers:

- Adam’s legal fees (even if Adam wins) = $100,000 to $2 million

- Beth’s legal fees ($100,000 to $2 million) + Damages ($millions)

- Adam’s and Beth’s time/stress/worry about the litigation — time that they’re not making music

- Other songwriters/labels/publishers worrying “does this song sound like something else?” So they produce less music.

Law should create certainty. Current copyright law — related to melodic copyright — is all uncertainty.

Conversely, this potential ATM Project position provides certainty:

Melodies = Math = Unoriginal/Facts = Uncopyrightable (or Thin Copyright)

If that’s adopted:

- There’s bright-line certainty.

- Everyone will know the rule.

- That certainty helps both Adam and Beth.

What do songwriters think about this?

Many, many songwriters have reached out to us. Some very famous. They have been overwhelmingly supportive. Songwriters are generally afraid of getting sued. Because if they’re ever sued, they see the current system’s overwhelming/insurmountable odds against them.

To put this in context: How often does Adam sue over melody? Some famous examples:

- Katy Perry (Flame)

- Led Zeppelin (Spirit)

- Coldplay (Satriani)

How many of those lawsuits do songwriters/musicians:

- …consider justified? (i.e., “Yeah, Adam is fighting the good fight!)

- …consider unjustified? (i.e,. “C’mon, really? It’s a coincidence. Adam is just trying to cash in. There are a million songs with that lick!”)

- …not know what to think, saying “Man, that’s a hard one — I hope I’m never in that situation.”

Law should give certainty. Current copyright law lacks certainty. Musicians/Songwriters should have clearer rules of the road.

- Today, all songwriters/musicians face uncertainty: “We might get sued from someone we’ve never heard of — who knows? Roll the dice.”

- Should the answer instead be this?

- “Well, the law says that…

- …if the only thing that’s similar is Melody X

- …or if you’ve never heard Song 1 (or if you don’t remember it)

- …then you should be fine.”

How would infringement claims proceed without melody?

Most legitimate copyright-infringement claims don’t need to rely on melodic building blocks. They can use other aspects of copyrightability. And for those that rely on melody alone, should those move forward?

- Honest question: Are courts the preferred way to resolve disputes — or for songwriters to make money? Should they be? Or should litigation be a last resort?

- Mechanical Royalties. People almost never sue over non-payment of mechanical royalties. Because the law in that area provides certainty.

- Performing Rights Organization (PRO) fees. Cases over not paying ASCAP/BMI/SESAC fees almost never go to trial. Just quick complaint, then settlement. That’s because the law in that area provides certainty.

- Ambiguity. Litigation is only necessary for areas of legal ambiguity. But if the law provides certainty, then the need for litigation goes away. Because where the law provides certainty, everyone knows the rules. No need to sue (or spend legal fees).

- In cases involving melodies, there’s more litigation. Why? Because of the uncertainty. The law is unclear. The rules are fuzzy. Or they favor Adam.

- Did Beth ever hear Song 1? “Who cares: Let’s sue her and roll the dice.”

- Is Beth’s Song 2 melody the same as Adam’s Song 1 melody? “Well, they use the same pitches, so it’s worth a shot. Doesn’t matter if we won’t find any evidence that Beth heard Song 1.”

- Lawsuit results like Katy Perry’s loss set a dangerous precedent — and uncertainty — for songwriters.

- The message: IF your song gets popular enough, AND Adam’s song has a similar melody (doesn’t even need to be identical), THEN you’re probably getting sued — and it doesn’t matter if you’ve never heard Adam’s song. (Katy Perry and her co-songwriters testified that they never heard Flame’s song.)

- The result: Given that uncertainty — only currently resolvable at the end of litigation (e.g., summary judgment or trial) — why WOULDN’T Adam sue? Given the uncertainty, NOT suing would be foolish. Roll the dice; see if you can get a settlement/judgment.

- Our All the Music work seeks to give the law — and songwriters — some certainty.

- Melody = Math = Fact = Uncopyrightable (or Thin Copyright)

But if melodies aren’t protectable, David Defendant could steal melodies without punishment!

If that’s one potential future, let’s think through those consequences. In fact we don’t have to think hard — because people do that all the time today: It’s called a “cover song.”

Cover songs’ copied elements. Let’s think about the cover song’s elements that copy the original:

- Melody, which is composed of:

- Pitch sequence (usually copied)

- Rhythm (sometimes copied, but not usually)

- Lyrics (almost always copied, though sometimes changed)

- Harmony/Chords (usually copied, though often changed)

- Timbre (sometimes copied, though often changed)

- Feel/Groove (sometimes copied, though often changed)

Everyone would agree: A cover song largely captures the “essence” of a song’s elements: Melody + Lyrics + Harmony + Timbre + Groove. A good cover song will also add the covering musician’s unique take, building on top of it. But for both verbatim/slavish covers and for unexpected covers, everyone probably agrees that a cover song copies nearly all of a song’s elements.

Commercial consequences. What effect does sales of a cover song eclipse (or even hurt) the sales of the original? Next to zero. In fact, they often help rekindle the audience’s interest in the original. (“I haven’t heard that song in years. Play it!”)

Even when an original artist re-records their song (e.g., to circumvent a label’s ownership of the sound recording rights, but not the underlying composition), the commercial effect on the original song’s sales is nearly nonexistent.

If zero effect for covers, what does that mean for melody alone? The discussion above is for covers (Melody/Pitch/Rhythm + Lyrics + Harmony/Chords + Feel/Groove).

Melody alone? Without lyrics? Without harmony? How much would that hurt sales of the “original” melody. If cover songs = next to zero, then “melody alone” = almost certainly zero.

In copyright litigation, damages can be measured by two factors:

- Original’s decreased value.

- How much did the new song decrease the old song’s commercial value/sales/streams?

- Example: How much did Vanilla Ice’s “Ice Ice Baby” decrease popularity of the Queen/Bowie song “Under Pressure”? Or did “Ice Ice Baby” introduce a whole new audience to Queen/Bowie?

- Substitution? Would someone say “I don’t need to hear ‘Under Pressure’ — I’ve got ‘Ice Ice Baby’!”

- New song’s increased value.

- How much did the old song’s element contribute to the new song’s commercial success?

- Example: How much did Katy Perry’s ostinato line increase its popularity — or was the song’s popularity more attributable to the pop star’s fame and the label’s formidable marketing machine?

Cover songs (Melody/Pitch/Rhythm + Lyrics + Harmony/Chords + Timbre + Feel/Groove) don’t decrease the older’s song commercial value. Cover songs are usually weak facsimiles of the original. In the commercial/artistic marketplace, cover songs usually lose.

Even more than cover songs, a totally different Song 2 that uses the same Melody X (pitch sequence and/or rhythm alone) doesn’t affect Song 1 a single iota. It’s not a substitute. The two songs aren’t even connected in listeners’ minds. Until a “gotcha” lawsuit.

Musicians/composers demonstrate their creativity — but through what output?

Here are potential categories of musical elements:

- TYPE ONE: MATH. Musical elements that today’s machines can crank out at 300,000 items per second (as we have, and will, with the All the Music project)? And tomorrow will create even faster/better?

- Melody/Pitches alone?

- Melody/Pitches + Rhythm?

- Melody/Pitches + Rhythm + Harmony?

- Melody/Pitches + Rhythm + Harmony + Timbre?

- TYPE TWO: HUMAN-ONLY COMBINATIONS. Combinations of elements that machines cannot yet replicate (and perhaps may never be able to)? Some examples:

- Melody + Lyrics

- Melody + Lyrics + Rhythm

- Melody + Lyrics + Rhythm + Harmony

- Melody + Lyrics + Rhythm + Harmony + Timbre

- TYPE THREE: ARTISTIC MUSICALITY

- Leaning on a note, then releasing at just the right time

- An unexpected turn of phrase (either lyrical or musical)

- The ache of a singers voice during a particularly poignant lyric

- Something that makes our hearts sing — even if we can’t put our fingers on the reason

- Many others that you’ll be able to list

- How many Type Two elements can machines replicate today? None.

- How many Type Two elements will machines replicate tomorrow? Unlikely during our lifetimes.

- TYPE FOUR: PHYSICAL EMBODIMENT

- A combination of all elements above — as embodied in:

- Live performances

- Recordings in any format (e.g., audio, MIDI)

- Cover songs and derivative works

- Scores and sheet music

- A combination of all elements above — as embodied in:

Copyright = government-created monopoly of 95 years to 145+ years

In the U.S., copyright duration is usually 100+ years (author’s life + 70, 95, or 120 years). So if a 20-year-old writes a song, then lives to age 95, the song is then protected for another 70 years — for a grand total of 145+ years.

That being the case:

- What musical elements (Types One, Two, Three) do songwriters think should be locked up as a government-created monopoly for up to 145+ years?

- What musical elements (Types One, Two, Three) do songwriters think should remain free as a songwriter’s tools?

- Scales/modes?

- Intervals?

- Pitch changes?

- Rhythms?

- Harmonizations?

- Timbre?

- Dynamics (e.g., crescendos, decrescendos)?

- Tempo (e.g., accelerando, ritardando)

- Expressiveness?

- Groove?

- If any Type One elements are locked up for 100+ years, then what effect will that have on music’s future?

- Today’s musicians/composers have fewer ways of making money than in the 20th Century.

- Lock up creativity? Should 20th Century musicians be able to put a stranglehold on 21st-century musicians/composers — for musical elements (e.g., melodies, blues scales, blues chords, “groove”) that the 20th century musicians “borrowed” (or more accurately “built upon”) from earlier generations?

- Recording’s 20th-century invention = monopoly? And because 20th Century musicians benefited from the happy historical accident of being born and working during the era when mass recording began (and copyrighting flourished) — from 1950s to 2000 — should that allow 20th Century songwriters to limit (or inhibit) new songwriters’ creative output until the year 2100 (and beyond)?

A potential solution

Below is one potential solution:

- Type One (music’s building blocks): Keep those as available to all. (No copyright.)

- Type Two (human passion/expression): Perhaps protect/monopolize this legally, though the question is how?

- “You leaned on that note like I did!”

- “You made the same unexpected turn of phrase!”

- “Your voice ached like mine did!”

- “You made listeners’ hearts sing like I did!”

- Type Three (recordings/scores): Limit lawsuits to Type Three — since they embody Type Two (expressing human creativity)

- Recording artists (and the recording industry) remain protected

- Performers remain protected

- Composers, Labels, and Publishing Houses remain protected

If melodies aren’t copyrightable, what happens to existing and future licenses/royalties? (e.g., Adam licenses to Javier)

Those are unlikely to be affected. Here’s a potential scenario:

- In 2020, Adam creates Song 1 (in English) containing Melody X,

- …then licenses Melody X to Javier, an emerging Hispanic songwriter

- Javier translates Song 1 into Spanish, recording/releasing the song

- Javier pays Adam licensing/royalties

- Javier later learns that melodies are facts, so Melody X is uncopyrightable.

Would Javier be entitled to reimbursement (from Adam) of (1) license fees and (2) royalties?

Probably not. Because Song 1 is more than mere Melody X.

- Adam’s Song 1 = Melody X + English Lyrics + Chords (probably) + Instrumentation (maybe) + Timbre (maybe) + many other things + magic

- Javier’s Song 3 = all of those + Spanish Lyrics = likely derivative work of Song 1

Javier’s licensing fees (for the derivative work) would probably continue to be justified, since the Song 1 is more than just Melody X — it’s the entire bundle of copyright sticks.

ACCESS: A $500k to $2 million question

Need to go to trial to prove a negative? “I’ve never heard that song”

Even if the courts/policymakers don’t accept the other aspects of the ATM Project’s arguments (e.g., Melody = Math = Facts = Uncopyrightable), they should still implement early-stage evidentiary hearings.

PROBLEM 1: COSTS. Innocent songwriters (e.g., Beth), to defend themselves, always need to pay legal fees for discovery and/or trial — where a song’s value is rarely worth the cost of defense.

- Whether Beth has access to Song 1 is almost always a fact question

- Fact questions usually aren’t resolved until (1) after discovery or (2) after trial

- That results in massive legal fees — even if Beth never accessed to Song 1

PROBLEM 2: FLIPPED BURDEN. Under current precedent, established by the George Harrison “My Sweet Lord” case (Bright Tunes Music Corp. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd., 420 F. Supp. 177 (S.D.N.Y. 1976)), the plaintiff’s standard burden of proof is flipped:

- Typical lawsuits: Plaintiffs bear the burden of proving defendants’ liability

- Copyright lawsuits under Bright Tunes (“My Sweet Lord”): Defendants (e.g., Beth) effectively bear the burden of proving that they never heard Plaintiff’s Song 1. That’s problematic for several reasons:

- Proving a negative is impossible

- Even after providing testimony that Beth has never heard Song 1

- …and even after Adam shows no evidence that Beth heard Song 1

- …a jury can still find that Beth must have heard Song 1

- See the Flame/Katy Perry “Dark Horse” case.

PROBLEM 3: SHAKEDOWN. Innocent, early-stage defendants (e.g., Beth) currently face a Sophie’s Choice:

- Vigorously defend their innocence/non-infringement, despite:

- …being forced to pay legal fees through Discovery, Summary Judgment, and Trial (i.e., because Access is a fact question)

- …bearing the (impossible) burden of proving a negative (BETH: “I never heard Song 1.”)

- Settle immediately, despite their innocence/non-infringement. This is common since:

- The burdens above are (1) flipped and (2) impossible to prove

- Beth’s song usually isn’t worth the cost of defense.

To remedy Problem 1, Problem 2, and Problem 3, courts might choose among two paths:

- Path 1: Music = Math = Facts = Uncopyrightable. This is the best solution. It fixes:

- Problem 1 (Costs)

- Problem 2 (Flipped Burden)

- Problem 3 (Shakedown)

- Path 2: Melodies are actually still copyrightable (i.e., melody ≠ math). All three problems (Costs, Flipped Burden, Shakedown) remain. But if courts choose this path, they should lessen innocent Beth’s burden by:

- Problem 1: Permitting early-stage evidentiary hearings

- Problem 2: Reverting the burden back on plaintiffs like Adam (to prove that Beth heard Song 1)

- Problem 3: Lessening the likelihood of a Shakedown scenario, since Beth can have an early-stage evidentiary hearing (and potential dismissal)— making successfully defending her innocence/non-infringement more economically viable.

Courts should choose Path 1. But if they choose Path 2, they can still make Access a more-even playing field.

SOLUTION: Early-Stage Evidentiary Hearing/Disclosure.

This early-stage procedure would include both (a) document disclosure and (b) testimony — limited to the extent to which Defendants Beth or David have — or have not — heard Song 1.

- Written disclosure/evidence from Beth and David:

- Writings (e.g., E-mail, text, Slack messages) mentioning Song 1

- Streaming history (e.g., YouTube, Spotify, Apple Music, Tidal)

- Other writings related to Song 1

- Testimony from Beth and David

This early-stage procedure might have four potential results:

- RESULT 1:

- Adam proves (through writings/testimony) that David had heard Adam’s Song 1, and/or was thinking about Song 1 when David wrote his song.

- That’s like Pharrell with “Blurred Lines.”

- RESULT 2:

- Beth testifies “I heard Song 1, but that was 20 years ago. I’d forgotten about it.”

- No writings/evidence showing any Beth access to Song 1.

- RESULT 3:

- Beth testifies “I don’t remember hearing Song 1, but even if I did, that was years ago — I wasn’t thinking of it.”

- No writings/evidence showing access to Song 1.

- That’s like George Harrison with “My Sweet Lord.”

- RESULT 4:

- Beth testifies “I’ve never heard Adam’s Song 1 in my life.”

- No writings/evidence showing access to Song 1.

- That’s like Sam Smith with “Stay with Me.”

One potential judicial solution, at the early stage:

- No evidence of access. IF Adam’ can’t prove Beth’s access or intent (e.g., #2, #3, #4), THEN the case gets dismissed (Beth never heard, or Beth had forgotten, Song 1.)

- Evidence of Access. IF Adam proves David’s access and/or intent (#1, shown through Testimony, streaming history, email, SMS,, WhatsApp, etc.), THEN the lawsuit continues: Discovery, Summary Judgment, and Trial.

That solution could balance two reasonable positions — of two reasonable songwriters:

- Adam songwriter’s right to keep David from stealing Adam’s song

- Beth songwriter’s right to avoid paying huge legal fees to defend a song she’s never heard (or doesn’t remember) in a finite melodic dataset.